This was the best failure I have had in a while.

I have the same, but intensified, test-taking issues that v4913 has. I’m glad that I had this test because I will be working very hard towards making this the absolute last time I failed this hard.

It all stemmed from the mindset.

Over the long break, I communicated with my fellow officers about whether or not I should make my high school math club’s team selection test for the Carnegie Mellon Informatics and Mathematics Competition. The three teams that we have signed up for are to travel to Carnegie Mellon in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania for an overnight car ride.

Eliana (one of my fellow officers) and I were going to write the problems, but later on, when I logged onto the document the night before, I discovered that Pavan (another officer) had already written up most of the test. I quickly closed the document and planned to take the tryout test during club time with other members.

Here’s how this went.

Our club room was too small to fit everyone in the room, so we moved to another room to take the test. There were about fifteen people maximum that came to take the test, but with makeup, someone would most likely be squeezed out (by the Pigeonhole Principle!). As usual, I took my folder, full of scratch paper and a pencil box.

I said a quick prayer before I started the test. I did Problem 1 in a matter of minutes, and thought I cleared it although I made a mental note to check. Already, I had noticed that a freshman to my side had flipped his paper before I did.

This was where things went downhill.

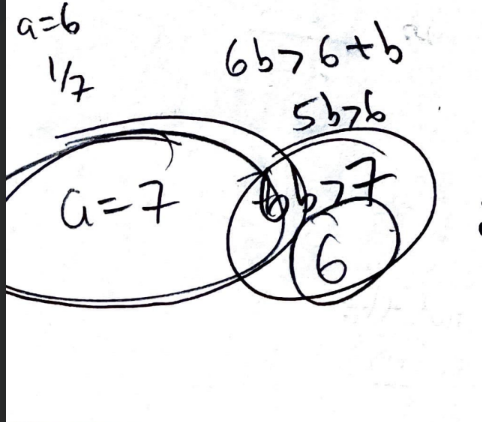

Already concerned by this, and telling myself that there are better underclassmen you have to beat, my bond with the problems plummeted down. I rushed through the first problem and put something like 2935, which was wrong because I omitted the case where a number could be 7. I cleared the second problem by solving for the correct common ratio, but instead put (1627) instead of

(2716), which cost me another point. Thankfully I got the third problem right (7350) and later on corrected the answer key that Pavan had.

However, the mentality I had going in the first minute of the test took a toll. I got stuck on problem 5 for a very long time, thinking that I had to beat the problem down. I thought of a string bijection for Problem 4 and put down 42 because I thought it was some Catalan bijection, but moments after the test I thought of the case where there are at least three consecutive moves of the same type, which shot it down.

Isn’t this a simple circle problem that I can solve? C’mon you gotta beat this.

I checked the time numerous (at least five out of six) times during the entire test. I checked the clock on the wall when there were forty, thirty, ten, seven, five minutes left. I tried to fight the time that was remaining and tried to force myself to solve problems with a few minutes left, hoping that God would give me a miracle.

Miracles don’t happen without the right mindset (and therefore the right actions).

Time ran out and I got up to distribute snacks.

I handed an aesthetic 1/10 to Pavan when he took my test.

What did I glean from this harrowing experience?

- When you start a test, it’s only you and the problems. Your number one goal is to learn how to solve the problems. Instead of treating them as impediments to success, try to think of them as your friends! They’re just a bunch of conditions that may not seem obvious at first, but once you get to know them you’re a lot likelier to solve them! Along with your internal battle against your “lazy” self, this was what worked. It’s your paper: own it. Treat it like a math worksheet! If you can beat yourself, you are much more likely to perform at your best and exceed expectations.

- Today, I kept thinking that I would need to beat the problems to get a great score. That is simply untrue. What about the underclassmen who are better than me? Screw them and everyone else in that room: that hampered my score my performance and my focus. You can’t make them leave, so you must get into your mind and ask why the **** do you care so much. On the AIME, I succeeded because I pressed on each problem with intense concentration. On the HMMT, when I was close to placing top 50, it was just the geometry problems (most of it, at least). Whenever I don’t place full concentration on what I’m doing, I’m extremely likely to make silly mistakes and become stuck in my methods.

- As for the personal focus, you shouldn’t be doing contests or swimming or reading or writing or whatever to beat the guy next to you. You’re not doing them to show off to the girls or to your best friend or your family. None of that. Nope: it’s a battle with your inner self (especially those who seem to choke under pressure). With math contests, a lot of it is not even about the math or your skill level. On my successful tests, I pushed past what I thought my limits were and found miraculous observations that solved the problem quite fast.

- Don’t worry about time. Because whether you have 30 minutes or 3 hours, you will have enough. As soon as I start worrying about time, my performance goes down the drain and I am unable to keep my focus on any single problem, especially if they are hard problems that I’m unsure how to do at first glance.

- I peeked at the clock at least five or six times this test. I was already feeling beaten down by myself that I had to exacerbate the situation by stressing myself with a time constraint of X minutes to solve Y problems. I hate that feeling when you’re pressured to perform well under a tight constraint. I just created that situation for myself today.

- When you are unsure about a problem, assume it is wrong. Check every problem you are unsure of: for every problem you got right, you must know that you got it right. This is part of the first point.

- During the Guts Round in HMMT, whenever I and my teammates did a problem and got conflicting answers, I assumed everyone was wrong. I made everyone check their answer again or come up with a different approach. This worked for a computationally heavy problem as I was able to agree on my answer with two other teammates, and we ended up submitting the right answer. Oftentimes the answers I’m the most skeptical about are the incorrect ones. Trust your gut!

Overall, doing well in math tests requires intense concentration. Even if you don’t think things are going well, you must remain calm and keep thinking about the problems. Stuff went badly in the first problem and because I wasn’t internally composed to calm down, check my answer for problem 1, and take my time (because in all probability, the test could be really hard!), everything afterward fell apart.

I analyzed my scratch work from the test and found that I made numerous conceptual and computational errors (most are marked in pen).

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1RInUBwgJGNZhLmh53tfzAWlfCjxq1tlM/view?usp=sharing

So even though I (most likely) did not make any of the three CMIMC teams we’re sending out (which is an excellent performance for an officer, I must say!), I learned a whole lot about myself. And I believe that next time, and the next, and the next, and so on, will be much better than this.

What worked? What didn’t work? Those are the crucial questions.