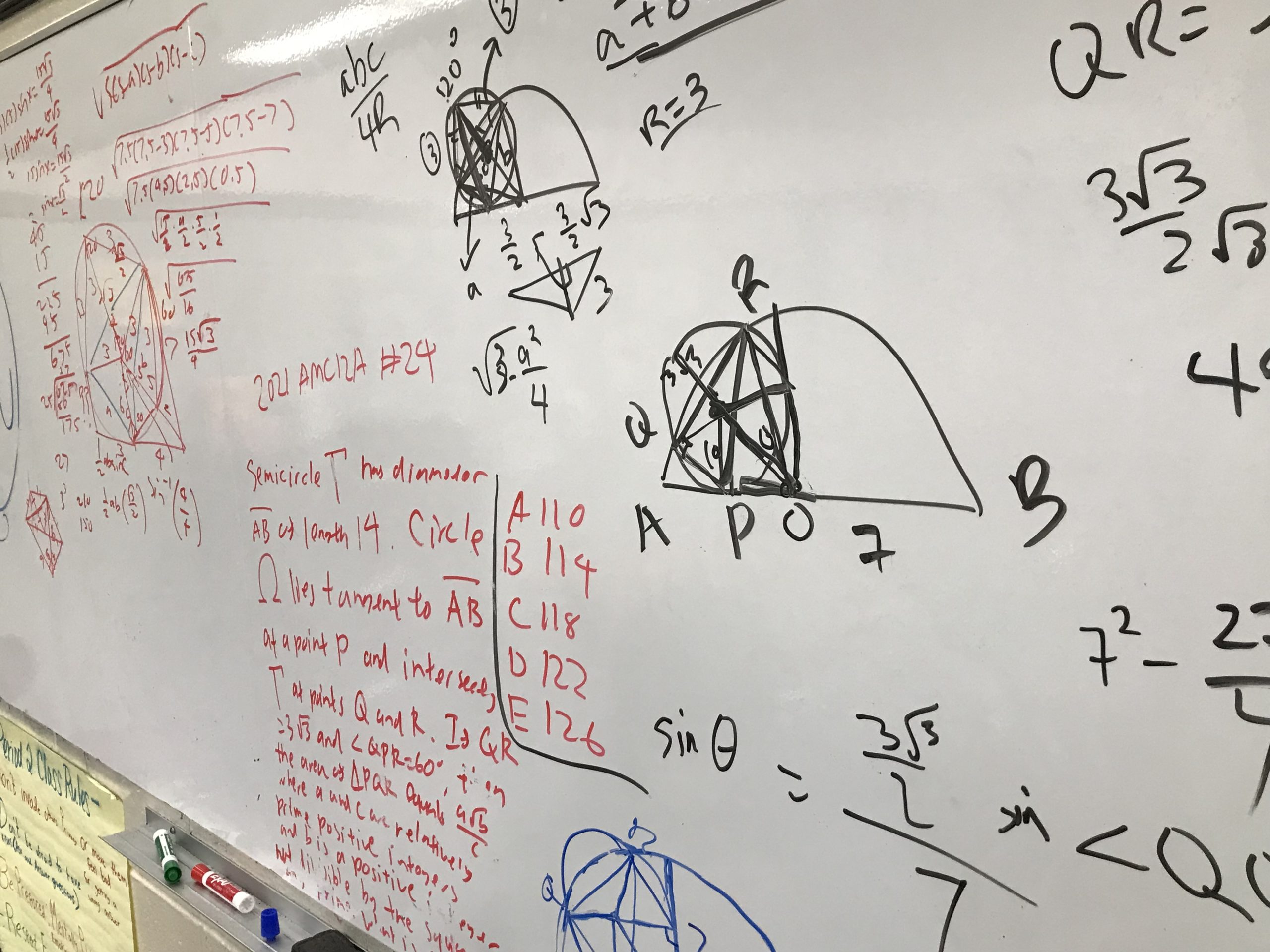

Image Credits: Me. Taken on June 7th, 2022. Me along with my math club friends were working on the 2020 AMC 12A #24 together. Spoiler alert: it’s an insanely hard problem.

I certainly know it’s no good to look at my past and it’s even worse to lament about what I “could have done” better. However, in my opinion, freshman year, being my first year actually getting involved in intensive math competitions, might be the year where I’ve learned the most and developed in terms of logical and mathematical reasoning.

I honestly don’t think I had enough confidence to write about this past year until this point, when the past season is actually over and the next is ahead of you.

Let’s first talk about last year (2021).

I actually had quite a confidence boost right before the AMCs in a competition called the MMATHS (Math Majors for America Tournament for High Schools). It was when I answered six out of twelve questions correctly, a pretty solid score compared to those of the AIME and olympiad qualifiers from my school, who scored in the 6 to 8 range. I genuinely enjoyed the rest of the rounds at that point (the mixer round was quite fun, managed to solve about three or four problems for my team).

However, two weeks after came the AMCs. To this day, missing the AIME by 1.5 and blundering the Fall 10B was one of the most dreaded memories by far of the school year. I was very confident that I would make AIME, scoring at least in the 100-110 range. But it never happened, did it?

I remember the 10A very vividly. I was working on problem #21 when the time was up. I counted the number of questions I had answered: eighteen! If I had no sillies, I would have a 118.5, a great score. But anything below would be too risky. I walked out confident that my efforts would qualify for AIME and failed a biology test miserably.

But I was shocked when I checked my answers against the AoPS forums. I had gotten four questions wrong which immediately pressed my score to 94.5.

I felt lost and went on to perform terribly in the 10B. It was after school and my mind was still on orchestra when the clock started. I don’t know what was going on, but right from the start my emotions took over and my brain didn’t want to respond. I was terribly stuck on the easiest questions, and couldn’t even get the first ten done. After time was up, I knew I had no chance for the 10B. I walked out of the math wing, got in my car, and started crying.

The real shocker (but such a surreal one) came on New Year’s Day – the day when the AIME cutoffs were out. I had secretly been hoping that the cutoff would be 93 or 94.5, but they were both 96 for both AMC 10s. I was basically ruined for that week.

Nonetheless, I didn’t really have any particularly “outstanding” scores after that, although I did outperform some people on the TSTs for the other contests.

What in the world did the AMCs teach me? I learned so many things.

Firstly, there are no guarantees in any competition; needless to say, in the real world. You can have all the practice in the world and have a great mindset, but still not qualify for AIME. Only training and practicing in a smart and deliberate fashion will at least increase your chance by a little. This also leads to the principle of not having confidence that you will do well until you have actually taken the test. Sounds a bit counterintuitive, but it should work.

But the most important part I got out of it was the mindset and training. Mindset first: I definitely had emotions when I took the AMC 10s. “What if I can’t solve this”, “this is too hard” – all of that BS has to go out the window and never come back again until you get your part done. The true winners are the ones who wins even in the face of hard times. When I took the 10B, they were testing the bell and announcements, and people still got 130s. That’s surely my problem.

Also, learning how to be calm down is a crucial skill. In a math competition, nothing else should come to your mind except the problems at hand; seriously, nothing else. See, it’s so easy to get distracted these days with social media that my generation of kids don’t even know how to read a long passage with concentration or even take a math test! This can actually be solved by spotting small distraction sources that kill your life, such as not checking your phone when you’re bored at school, grinding problems with concentration and doing a task well. Yes, do the task well – and DON’T DO IT WRONG GEEZ! Calming down also means solving easy problems quickly and accurately – you don’t want to be like me who got this problem wrong because I “thought” I was correct and randomly chose an answer!

Now, the training part is important: not only do you have to do hard problems, but if you haven’t qualified fo JMO or AMO before in your whole life, you need to know how to get a 130+ score on the AMC. It’s a speed-based competition, it’s not going to be easy, but somehow you’ve got to get to the top of the ladder, where all of the JMO/AMO qualifiers score. This can be achieved by doing lots of mock AMC problems and not purely AIME problems because speed is important.

It’s also very important to enjoy the glory of math itself. Self reminder to write a whole post on this.

The other important thing about competitions is the concept of failure. I had clearly established an idea I had abstractly formed in my mind with the book Mindset: The New Psychology of Success by Carol Dweck. In this book, Dweck strengthens the view that the growth mindset will get you to grow as a person as a whole rather than only focusing on the results. No one really likes to fail, but the book proposes that the people who really succeed use failure to propel them even further than they have been before. Treat failure as a friend!

Failure has actually taught me so much more than the times when I have succeeded. It was around the time of this year’s ARML that I realized that failure isn’t bad. It really isn’t – getting a three out of ten on the ARML meant that I needed to practice harder problems as well as do the medium-difficulty problems faster. Now I see why so many people say “I failed” when they actually performed badly, but don’t do anything about it!

There are a lot more nitty-gritty details of competition math. For the most part, many of these principles can be applied to real-world situations.

But no matter what happens, it’s so important to move on despite all your past mistakes. After each contest this past year, I’ve moved on and proceeded to grind a bunch before the next competition. And again I didn’t do well. But each time I fell, I got up again. Crying’s just a waste of time – before you know it, your emotions can take up an hour of your life when you could have grinded.

With all of these principles in mind, the goal of making USA(J)MO is still intact. AMC 130+, AIME 9+ are still my unachieved goals.

Will this be the year where I make the breakthrough? And no, this time I actually mean it.

There are still many opportunities, such as the HMMT and the ARML. If I score well on those (top 20 in the nation?), then I could potentially be qualified too.

However, it won’t come until I grind enough problems, gain a solid theory, and achieve the right, positive growth mindset.

This school year will be the year of no fooling around and no distractions, and it’s not only for math!

There are literally so many aspects to competition math I would like to add, but I will add these little tidbits in a future post, or else this would get too long.

Hope you got a little taste of my philosophy. Peace out!